FROM: First Three Years

- There has been a national trend over the past decade of reducing playtime as an integral part of the school day. This trend is most easily observed in the reduction and, in some cases, elimination of recess; however, there are more subtle changes throughout the school day that reduce children’s opportunity to play. First, the approach to early education that naturally incorporated play into the school day is shifting toward a more academically oriented instructional approach as new standards for reading readiness have changed for even kindergarten students.9 Second, in many districts, there is less school time allocated to the creative arts and physical education.9,43,44 These subjects contribute to a well-rounded education for a variety of reasons but share some of the benefits of play. They allow for a break from the standard academic subjects, foster creative and physical expression, and teach relaxation and stress-reduction skills that will last a lifetime.9,13 Finally, even after-school activities have shifted away from play and physical activity and toward being an extension of academics and a space for homework completion.43 This report focuses on reduced recess for illustrative purposes.

- Children cannot play safely outside of the home in many poor communities—urban, suburban, and rural—unless they are under close adult supervision and protection. This is particularly true in areas that are unsafe because of increased violence or where other environmental dangers exist.

- Although lower-income parents have the same desires for their children to succeed and reach their full potential as do parents with greater economic and social assets, they must focus primarily on the family’s day-to-day survival. When food and shelter are at risk, ensuring time for the children to have free and creative playtime may not be a priority. Economic hardship is a major obstacle for these families, in which the parents are more likely to have a lower educational level or be single heads of households. Minority households (black and Hispanic) and immigrant parents are at increased risk of having children who live in poverty.

FROM : American Meritocracy Is Killing Youth Sports by the Atlantic

- “The decline of youth sports participation is the sort of phenomenon that seems exquisitely tailored to exacerbate fears about the state of American childhood. One might suspect that the falloff is the result of children gravitating to video games, television, and other electronic distractions that don’t require an open field or a court. Perhaps athletics is just another legacy institution that can’t compete for attention anymore, like church, community centers, and bowling leagues.

But dig into the numbers, and a more complex, two-track story emerges. Among richer families, youth sports participation is actually rising. Among the poorest households, it’s trending down. Just 34 percent of children from families earning less than $25,000 played a team sport at least one day in 2017, versus 69 percent from homes earning more than $100,000. In 2011, those numbers were roughly 42 percent and 66 percent, respectively.

This isn’t a story about American childhood; it’s about American inequality.” - In short, the American system of youth sports—serving the talented, and often rich, individual at the expense of the collective—has taken a metal bat to the values of participation and universal development. Youth sports has become a pay-to-play machine.

FROM: Why Low-Income Kids Miss Out On Play by Elahe Izadhi

- (Reported 2012) Increasing the focus on academics and allotting less time for physical activity is a national trend. But the AAP report found that low-income school districts face greater cuts to recess and physical education because they are under pressure to reduce academic disparities. Nationwide, recess has been cut from one-third of schools with the highest poverty rates. Even after-school programs are shifting focus from creative and physical activities to homework help, often making them just an extension of the school day.

- There are fewer playgrounds in low-income, urban communities, or they may be underused because of a fear of violence Cities have less green space than the suburbs, so playgrounds are one of the only places where children can roam around freely and play. Obviously, if there aren’t many around, you don’t have as many chances to play.

- Making sure your kids get outdoor playtime may not be your priority if you’re working multiple jobs or constantly stressed about bills, housing and food.

FROM: Children in Poverty Need Opportunities to Play from American Academy of Pediatrics

- “For children facing the challenges of poverty, play is such an important tool to help them build the resilience that they need,” said lead author Regina Milteer, MD, FAAP. “Using their imaginations, fantasizing, and trying on grown-up roles helps them to take on their fears and create a world they can master.”

- Socioeconomic challenges can keep children from enjoying these important benefits for three main reasons:

- Cuts to recess and other school-based play or creative programs affect schools in lower-income communities disproportionately.

- In low-income neighborhoods, parks and play spaces may be lacking, and those that do exist often are unsafe due to violence or environmental dangers.

- Parents who need to focus primarily on their family’s day-to-day survival often do not have the time, energy or resources to spend on play.

FROM: Why It’s So Terrible That Poor Kids Aren’t Getting Enough Playtime by Amy Norton

- With a lack of safe places to roam, poor kids in cities are missing out on unstructured play, which is necessary for proper development.

FROM : Right to Play. org

- All children deserve a place to play, without fear, ridicule or frustration. Children with disabilities are often denied this pleasure.

FROM: Social Class & Sports by Taylor Hall

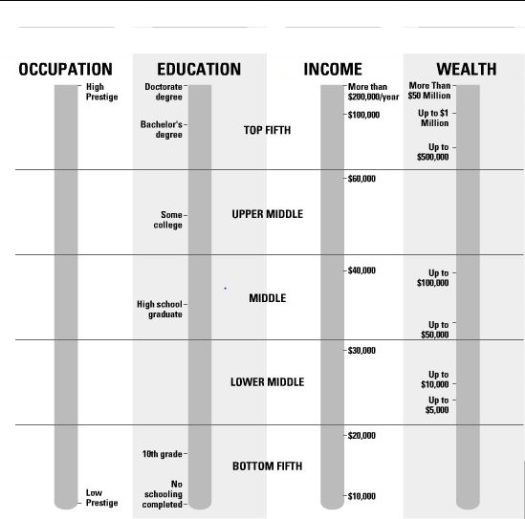

- In America, we like to think that sports transcends social class, but that is all too naive. Research has shown social class to have a direct relationship to sports involvement. Social class largely defines the types sports individuals choose participate in, their level of involvement, and affects their chances of success in the sport. Often times, sports are a reflection of social class. Despite the ubiquitous role class plays in sports, it is full of complexities and a difficult concept to explore.

FROM: The Paradox of Social Class and Sports Involvement: The Roles of Cultural and Economic Capital by Thomas Wilson

- Studies in the sociology of sport have found that the higher one’s social class, the greater is one’s overall involvement in sports, but the less likely is one’s involvement in what have come to be called `prole’ sports.

FROM: Classism in Sport: The Powerless Bear the Burden by D. Stanley Eitzen

- In reality, sports, just as the other instuttions of society, provdie a setting where the “poor pay more.”